Thanks to Tammy and her fellow editors at Hong Kong Studies for inviting me here today, and to CUHK for hosting this wonderful event. It is a pleasure and an honor to be able to talk about my work at Bleak House Books at the first ever symposium for Hong Kong Studies.

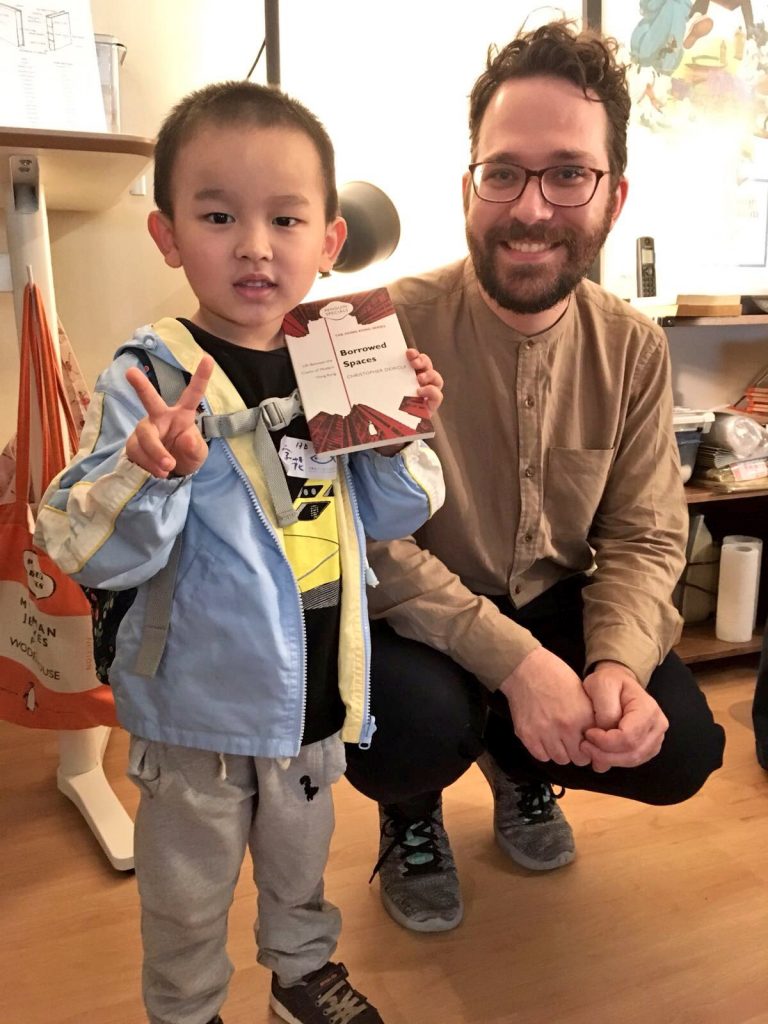

Today is a very special day for me, not just because I get to stand before a bunch of strangers and force them to listen to me talk about myself. It also happens to be Charlie, my son’s birthday — he turns seven years old — and I’ve promised Charlie that I’d be back in time for his birthday dinner tonight. So for purely selfish reasons I will try to keep my remarks brief and to the point.

As some of you may know I am the co-founder and owner of Bleak House Books, an English-language independent bookstore in Kowloon.

Jenny, my wife, is the other co-founder of Bleak House Books, but she has a real job as a college professor. So I have for better or worse become the face of the bookshop. To borrow from the recent testimony of Trump stooge and Steve Bannon look-alike, William Barr: Bleak House Books has become my baby.

Just like a baby has his or her moment of conception, there was a moment of conception for Bleak House Books as well. That would have been spring of 2016 when my wife and I and our 2 kids were still living in the United States. I had my own solo law practice doing criminal and civil rights work. My wife was teaching at Georgia Tech but had been offered a job at HKUST, which she accepted. So it was off to Hong Kong for the family.

I decided that rather than practice law in Hong Kong I would do something different. I didn’t know what I wanted to do next but I did have some criteria for what I wanted to get out of any such job. In my mind my next career had to be challenging, creative, and community-oriented.

Opening an independent bookstore, in the age of Amazon and Book Depository, and in a city that’s notorious for being a ‘cultural desert’ — an unfortunate and grossly inaccurate label by the way — seemed to fit the bill.

In December 2016 we moved to Hong Kong, and in February 2017 Bleak House Books was born.

At first we really just existed on paper. We had no physical space, no books, no website, and no customers. That would all change, of course, but not without a healthy dose of patience and fortitude.

You know what’s another unfortunate nickname that’s been given to Hong Kong? Capitalist paradise. It’s a paradise perhaps if you’re a capitalist with money to burn and others to do your bidding, but for regular people like myself, starting a business in Hong Kong from scratch was like taking a college entrance exam for the very first time: it was a painful, anxiety-inducing process that didn’t really make sense but you did it anyway because you had to.

For example, it took me almost an entire year to open up a business account for the bookshop at our local bank. We had to supply all sorts of information about ourselves and the bookshop to the bank before they would even look at our application. Once they started reviewing it the slightest discrepancy or question mark would cause the application to be sent to the reject pile, and we would have to start from square one again. The process was set up in such a way so that it seemed like we were asking the bank for money, when, in reality, we were trying to do the complete opposite: which was give them some of ours!

But I digress. The theme of today’s event, I am told, is the ‘neighborhood’. And my job is to talk to you all about what Bleak House Books has done to, and I quote, “build [a] creative, literary, culturally rich, safe and inclusive neighbourhood[].”

It’s humbling to think that Bleak House Books, now in only its second year of operation, might be considered a force capable of helping to build a neighborhood, let alone one that has pretensions of being ‘literary’, ‘safe’ or ‘culturally rich’. The sale of books does not a neighborhood make. And at its core, that is what we do at Bleak House Books: we sell books.

So what do we do at Bleak House Books, aside from selling books, that one might consider beneficial to the ‘neighborhood’ in a literary sense? First we support local artists and writers. We sell their works at the bookshop. We promote their causes if they have one. And we tell our readers about who these artists are and where they come from so that it might inspire others to take the plunge.

We’ve been lucky enough to have met artists and writers from all walks of life whose works run the gamut. For example, we have awesome poetry collections by Tammy Ho Lai Ming and Eddie Tay. We also have award-winning photography books and kids books created by some very talented and dedicated individuals: Agnes Ku, a sociology professor at HKUST and Ya Chin Chang, a young local artist, to name a few.

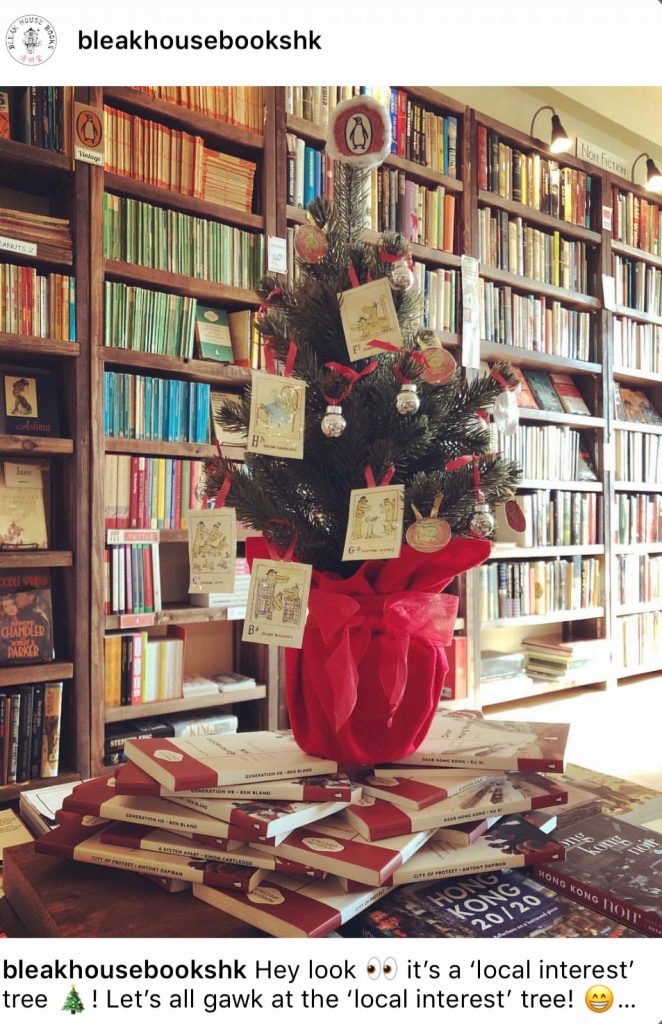

Something else we do at the bookshop is we offer our physical space to people who want to use it for events like book launches, poetry readings, and book club meetings.

After all neighborhoods need space too. Yes, they also need people and culture but without a discrete physical space you end up with the Wild West or maybe Twitter. That’s especially true for Hong Kong where there never seems to be enough land to satisfy the needs of the public. Housing, as we all know from news reports, is one of those needs. But so is art, especially when the artist is someone who is not famous, well-connected or independently wealthy.

But in today’s sensitive political climate the simple act of letting someone else use our space for an event can be fraught with difficulties and even risks.

Case in point, and we have Tammy to thank for this — thank you Tammy — Liu Xiaobo.

Last year Tammy asked if we would host an event entitled Liu Xiaobo Elegies on behalf of the literary journal Cha and PEN Hong Kong. When she asked I said yes without giving it much thought. In my mind and being from the U.S., holding an event to commemorate the death of a well-known and important human rights activist and political prisoner is natural, appropriate and uncontroversial; much as if we were to hold an event at the bookshop to commemorate the death of Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King, Jr.

Little did I know though that just hosting an event about someone who might be considered a critic of the Chinese Communist party can call into question my own political loyalties — not that I have any to speak of — and that that would somehow make me a target.

‘Don’t do it’, someone told me. ‘You’re putting yourself and your family in danger’, said another. We still held the event, of course, to a standing room only crowd, and I survived to tell the tale. But I feel like a part of me died in the process — the part of me that was taught from very early on that neighbors should be able to talk about their differences openly and that neighbors should not be afraid of each other.

Because that’s what China is to Hong Kong; right? A neighbor. Geographically. Historically. Economically. And yes even culturally.

And if we’ve learned anything from history it is that bad things happen when neighbors stop talking to each other. I won’t get into specific examples — that’s beyond the scope of this talk and, frankly, we all know what some of them are. I will say, however, that given the present climate of fear and polarization that exists here in Hong Kong and beyond the neighborhood needs more not fewer forums for open and honest dialogue.

I’ve talked about supporting local artists and hosting events as two things we do at Bleak House Books to help create an open, inclusive and culturally rich neighborhood. Is there anything else that we do? I’m glad you asked because the answer is yes.

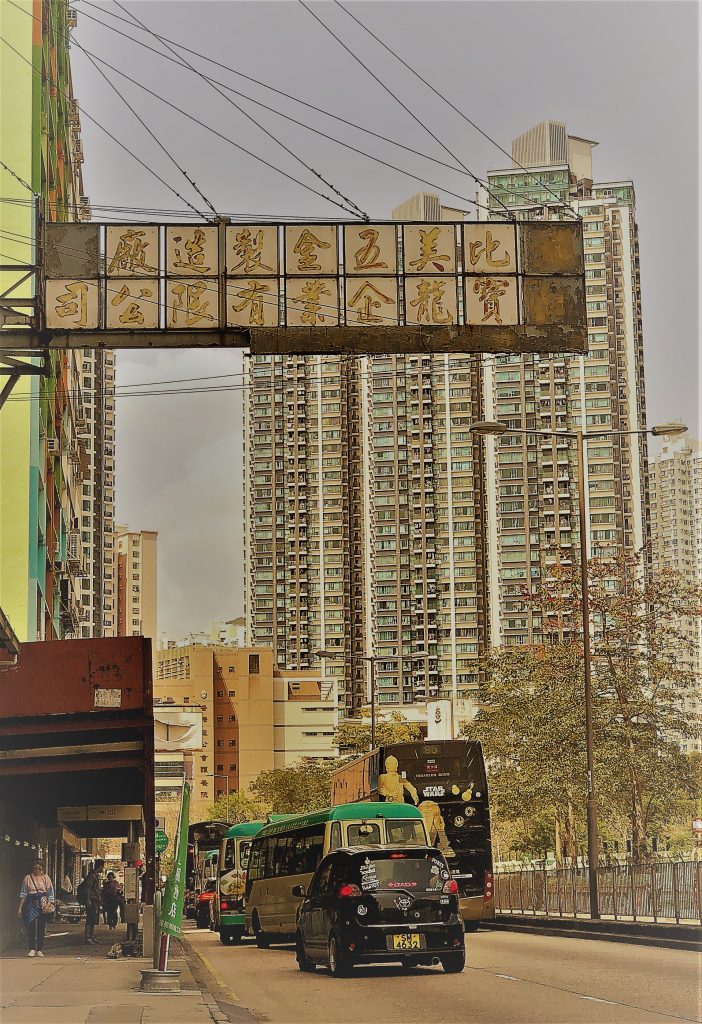

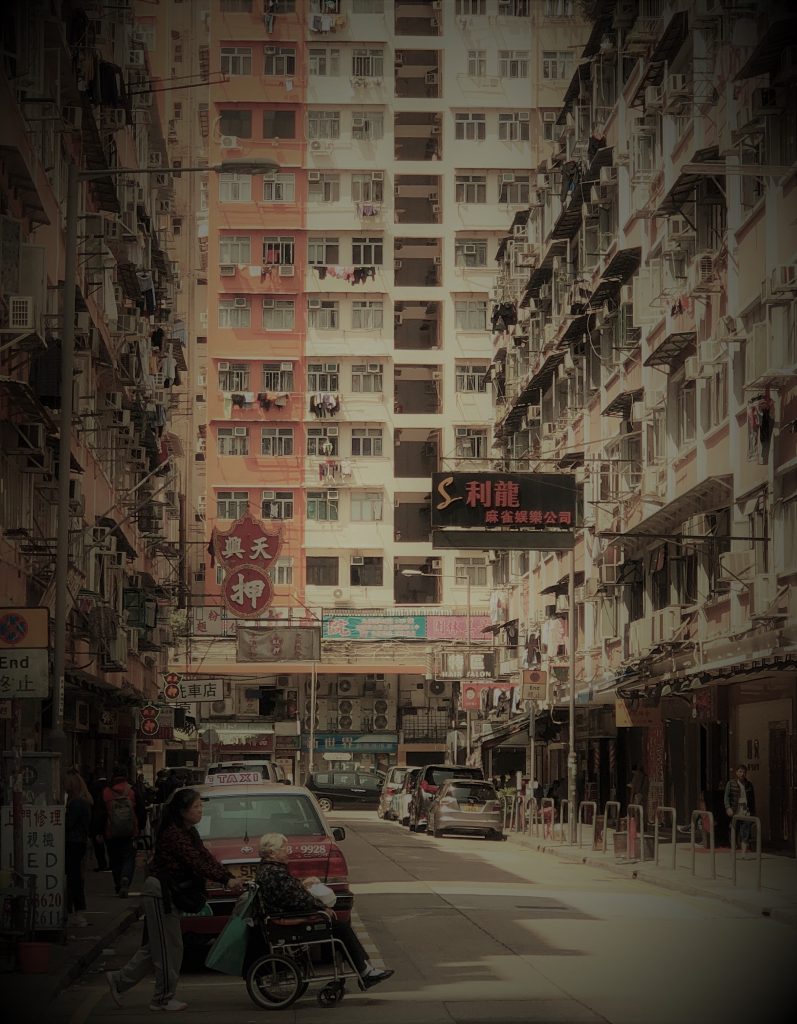

It may come as a surprise to some of you that our bookshop is located on the 27th floor of an office building in San Po Kong, a working-class, semi-industrial area of Kowloon, near the old Kai Tak airport. It’s a location that our past customers have described as being ‘far’, ‘out of the way’ and even ‘bizarre’.

There’s a lot of interesting history to San Po Kong though. We didn’t know much about it before we decided to open the bookshop there. But we came to learn a lot about the history of our new home from neighbors, customers and friends.

For example, did you know that San Po Kong used to be home to one of the biggest movie theatres in Hong Kong? Or that through San Po Kong flows one of few Spring-fed nullahs in Hong Kong?

As the name itself implies San Po Kong used to be just plain old “Po Kong” — the ‘San’ in San Po Kong means ‘new’ in Chinese. After World War II the Brits redeveloped Po Kong from an agricultural settlement into an industrial center, and gave it the name it has today: San Po Kong.

The area also played a central role in the riots of the 1960s. In 1967 workers at an artificial flower factory in San Po Kong clashed with their employers over poor working conditions. This dispute led to still more clashes, mostly between Communist sympathizers and the government, culminating in what would become known as the Leftist Riots of 1967.

The San Po Kong of today is very different from the San Po Kong of the 60’s. Gone are the factories, smoke stacks and the horde of workers who used to stream down Tai Yau Street, one of the main thoroughfares in San Po Kong, on their way to and from work. Today’s San Po Kong is sleeker, quieter, and, on the whole, more expensive.

Even so a lot of the San Po Kong of old remains. The buildings and the people who inhabit them are still decidedly working class. And our neighbors there are the types of folks who will, under normal circumstances, never step foot inside a bookshop, let alone one that sells vintage, English language books.

For example we have a neighbor downstairs in the building next to ours whom we call Si Fu. Si Fu is an 80 plus year old mechanic who still uses an abacus and takes cat naps inside his clients’ cars at lunch time.

Still it is important to me that our neighbors know we exist — not necessarily as purveyors of fine books — they can care less about what we do for a living — but as fellow Hong Kongers who have put down roots in their neighborhood. Because at the end of the day that to me is what a neighborhood is about: human bonds formed by a shared purpose and a common culture.

So if you see me shooting the breeze with someone on the street or having an afternoon drink at our local bar just know that I’m actually hard at work, building a stronger, more inclusive neighborhood — one bond, or maybe one drink, at a time.

Thank you all for listening to me today. I apologize if I put anyone to sleep. If you are such a person please see Tammy afterwards. She will see to it that you get a full refund of your admission fee.

Thank you.