a talk originally delivered by Albert Wan on 28 Nov. 2021 at Hiding Place bookstore in Sai Wan, Hong Kong; the images that follow are taken from the slide show that was shown in conjunction with the Nov. 28th talk — AW

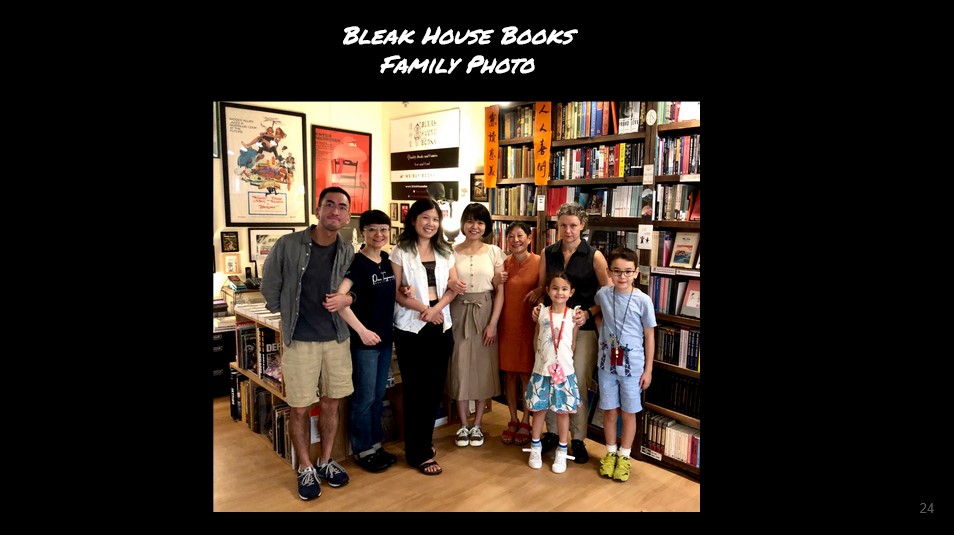

When Susi first asked me to give this talk it was at the bookshop during its last days, after I had announced that Bleak House Books would be closing for good. Susi came to the bookshop for one last visit and I was there doing bookshop stuff. She told me about her involvement with Peace Generation and how she thought it would be interesting to get the perspective of a bookseller on the subject of peace. I’m not sure I saw the connection back then and my thought actually was that Susi was feeling sorry for me about having to close the bookshop. And that was the real reason she had asked me to give this talk.

But it turned out that she was serious, and a few weeks later both Susi and Fiona gave me a thoughtful online presentation about Peace Generation — its story, its mission, and also some of the challenges they thought Peace Generation might face in attracting an audience in Hong Kong today. I listened. I asked a few questions. And I made one or two points of my own. At the end I thanked them both for being so generous with their time and their hearts.

That I’m here today means that I did at some point agree to give this talk. But I’m still not sure I see the connection between bookselling and peace. In fact, if you really want to know, I’m only here for the free beer. IS THERE FREE BEER?

Before I became a bookseller, I was a lawyer. Being a lawyer taught me about the importance and the power of storytelling. I mostly handled cases involving civil rights or human rights violations. And the people who came to me for help because of these issues always had stories to tell about how and why they felt they were wronged in some way. My job as a lawyer for the clients whose cases I took up was to tell their stories for them to people who had the power and ability to make things right: an opposing attorney, a judge, a jury, a government official, or even a complete stranger.

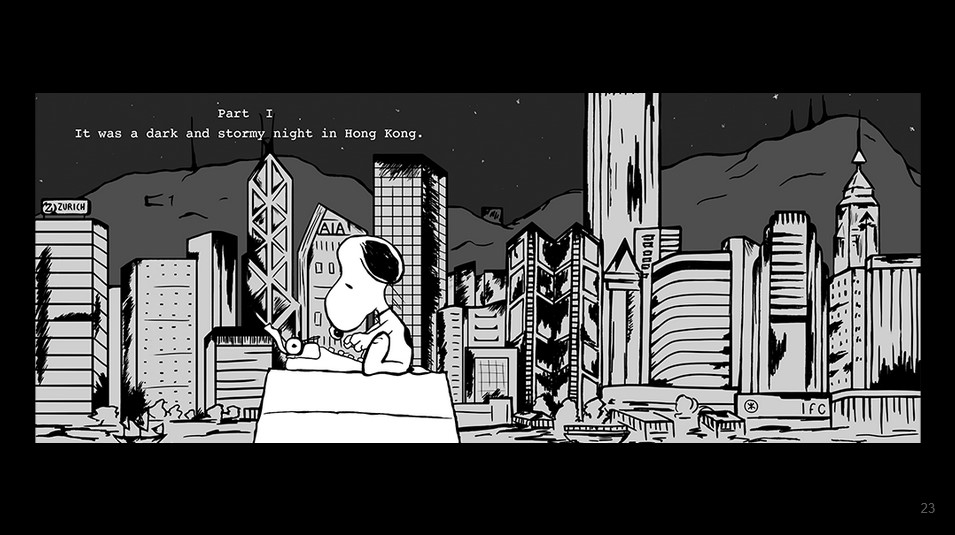

So I am going to start today’s talk with a story. Unlike the stories I used to tell on behalf of my clients, this one doesn’t have to do with anyone I know personally. Nor am I asking for anything in return for telling this story, except perhaps for your patience and ten minutes of your time. In other words, I hope you don’t fall asleep so early in my talk.

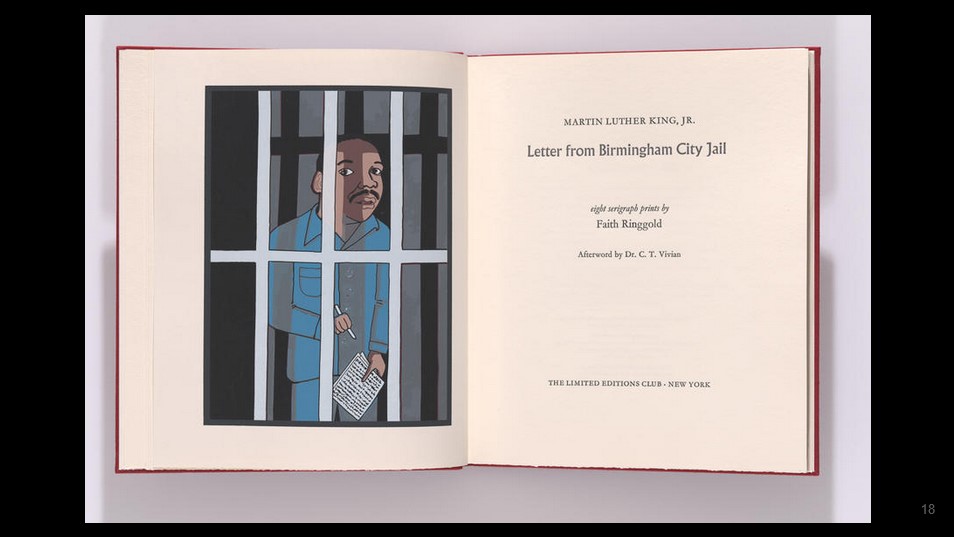

The story I want to tell has to do with the text of today’s talk which is Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’. It is a story about struggle, compassion, violence, and, of course, peace.

First a bit of geographical and historical background. Birmingham, where Dr. King wrote his letter, is a city in the state of Alabama, which is in the southern part of the United States, a region some Americans might refer to as the ‘Deep South’. Alabama is one of several states in the Deep South that has a long history of racism against blacks.

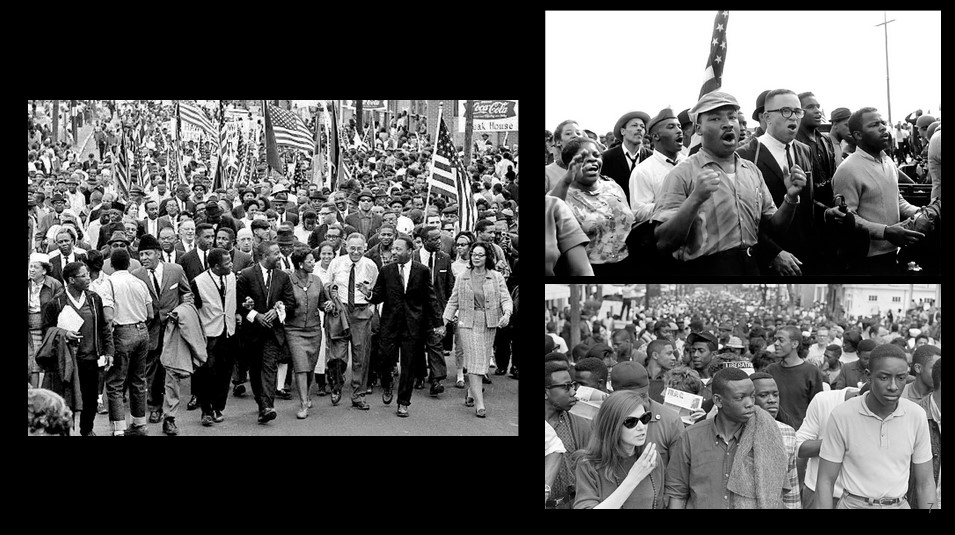

In the late 1950’s, more and more black Americans and some white Americans as well, began speaking out about the troubling wave of racist policies and violence that had then become the norm in many places in the United States. What started as sporadic and discrete acts of protest by individuals and small groups eventually grew into a broad, well-organized national movement which sought to create a society in which blacks would have the same rights and freedoms that whites have always enjoyed. The movement had many supporters and leaders with Dr. King being the most famous of those individuals.

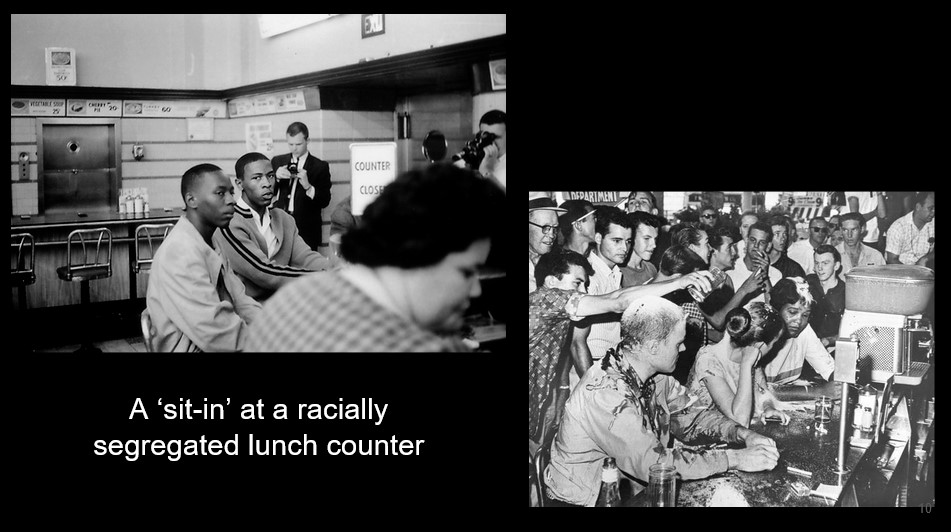

One of the things people in the movement did to challenge and potentially overturn racist laws and policies that were on the books at that time was to organise and attend peaceful, nonviolent protests. Often these protests involved actions in which the protestors would openly yet peacefully defy laws that were not only racist on their face — for example, a law that prohibited blacks from eating at the same lunch counter as whites — but also defy laws that were racist in the way they were applied — for example when the police refuse to give a permit for a protest march claiming it is unsafe but really because they disagree with the message or politics championed by the protestors.

In April 1963 Dr. King helped organize a large protest movement in Birmingham, Alabama, with the specific goal of forcing the city’s private businesses — its department stores, restaurants, barber shops, etc — to repeal their racist policies against blacks. At that time Birmingham was known throughout the United States as being one of the most segregated and racist cities in the country. And the grand strategy was that if Dr. King could achieve even a modest victory in Birmingham, it would go a long way toward changing the laws and cultures in other American cities.

The campaign would consist of a series of public direct actions like marches, boycotts and other activities that hopefully would call the nation’s and also the world’s attention to Birmingham’s racist treatment of blacks.

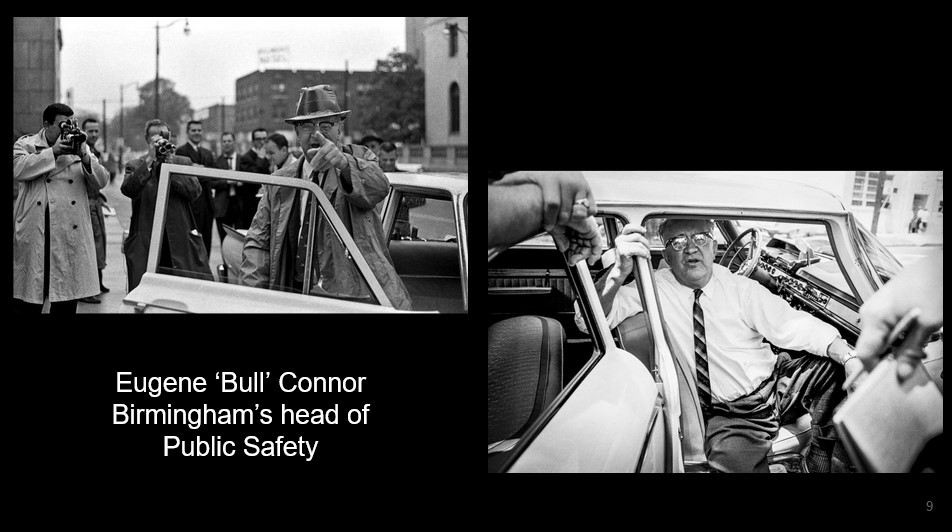

But Dr. King and his allies faced many challenges in Birmingham. There was Eugene ‘Bull’ Connor, the city’s notoriously powerful, arrogant, combative and racist head of public safety who controlled the police and fire departments among others. A number of Birmingham residents, some otherwise sympathetic to the civil rights cause, also disliked the fact that people like Dr. King, who did not live or work in Birmingham, were coming to their fair city to conduct potentially disruptive and violent demonstrations.

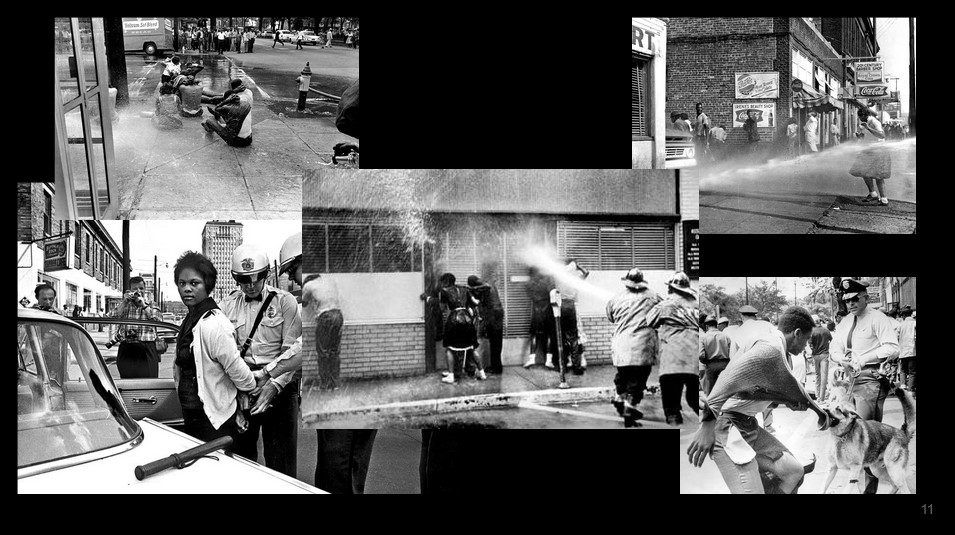

It was no surprise then that when the campaign eventually got under way in Birmingham it was met with fierce resistance by city officials and residents alike. Protestors who marched in the streets were brutally attacked by bystanders and racist thugs, while police officers either turned a blind eye or were ordered by their superiors not to respond at all to the attacks. Black protestors who peacefully insisted on service at businesses with racist policies — a tactic known as a ‘sit-in’ — were denied service and in some cases cursed at and spat upon. ‘Bull’ Connor issued orders that saw police use attack dogs and firefighters water cannons on protestors, many of them school age children.

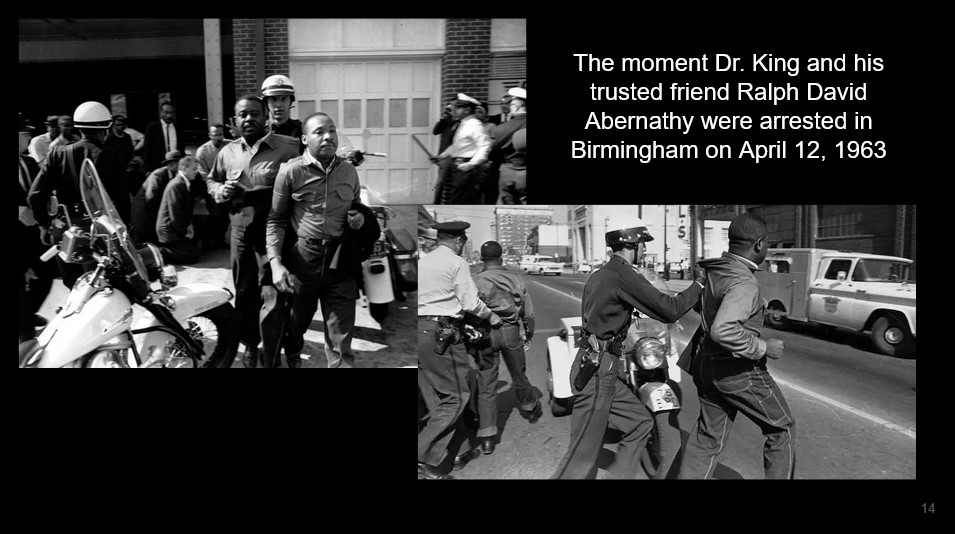

For Dr. King, the decisive moment in the Birmingham campaign came when city officials applied for and received a court injunction that prohibited further protests in the city. Dr. King and his trusted friend and ally Ralph David Abernathy had already planned to attend a protest march in a show of solidarity with fellow civil rights protestors when the injunction was issued. And with this new law on the books, Dr. King risked immediate arrest if he went ahead with his plan to attend the march.

The big question was whether Dr. King would disobey the injunction by sticking to his original plan to attend the march. At first the answer seemed obvious: yes. To Dr. King, the injunction was the product of an overly compliant court perpetuating an unjust system. So in violating the injunction, Dr. King would, in effect, be furthering the cause of the civil rights movement. It would be the kind of civil disobedience that Dr. King preached about and put into practice so often during his adult life.

But the path of civil disobedience involved a greater risk than just a few nights in jail for Dr. King. After the court issued its injunction, news broke that the movement had run out of money with which to bail out the hundreds of protestors who were already behind bars, many of whom were arrested on spurious charges. Dr. King was one of the few people who could change that. He was famous, he was eloquent, he was by then a household name. And if anyone could raise the funds necessary to bail out the protestors it was Dr. King. But he wouldn’t be able to do any of that sitting in jail. At the same time, other protesters and allies who were not in jail waited eagerly to march with Dr. King on the streets of Birmingham which he promised them he would do.

Dr. King was, at that moment, what you would describe as a person between a rock and a hard place. If he stayed away from the march he would be seen as weak and even hypocritical. But if he marched and got arrested he wouldn’t be able to help the many protestors who went to jail on his watch. A meeting was called with 24 other civil rights leaders and allies at the famous Gaston Motel, a black-owned business and central meeting place for leaders of the Birmingham campaign. Dr. King himself recalled in his book ‘Why We Can’t Wait’ the moment when he had to decide what to do and this is what he wrote:

I sat in the midst of the deepest quiet I have ever felt, with two dozen others in the room. There comes a time in the atmosphere of leadership when a man surrounded by loyal friends and allies realizes he has come face to face with himself. I was alone in that crowded room.

I walked to another room in the back of the suite, and stood in the center of the floor. I think I was standing also at the center of all that my life had brought me to be. I thought of the twenty-four people, waiting in the room. I thought of the three hundred, waiting in prison. I thought of my Birmingham Negro community, waiting. Then my mind leaped beyond the Gaston Motel, past the city jail, past city lines and state lines, and I thought of twenty million black people who dreamed that someday they might be able to cross the Red Sea of injustice and find their way to the promised land of integration and freedom. There was no more room for doubt.

I pulled off my shirt and pants, got into work clothes and went back to the other room to tell them I had decided to go to jail.

“I don’t know what will happen; I don’t know where the money will come from. But I have to make a faith act.”

From the essay New Day in Birmingham, collected in Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King, Jr., pp. 72-73 (Signet Books 1964).

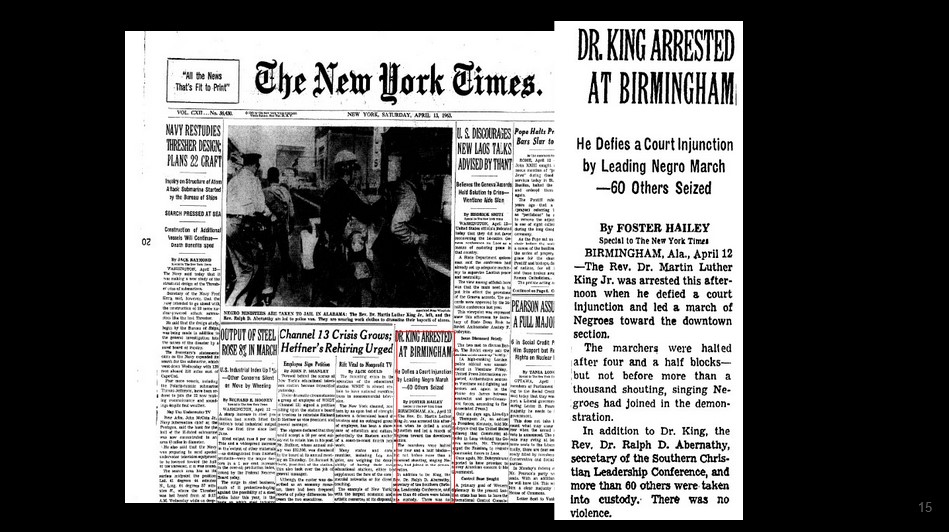

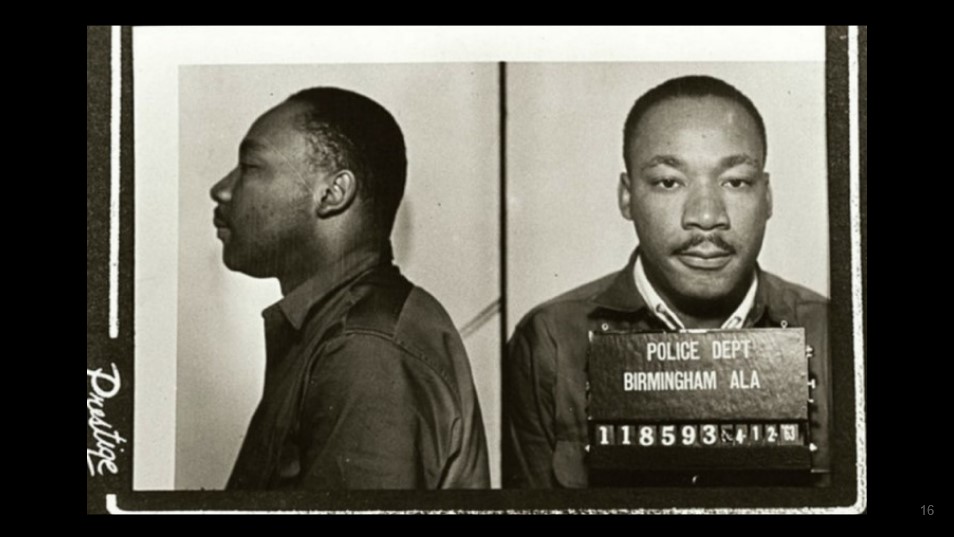

Dr. King made this decision on the morning of Good Friday and later that day he joined fifty other protestors on the streets of downtown Birmingham. They held hands, they marched, they sang. After walking seven or eight blocks Dr. King and the rest of the protestors were arrested under the orders of ‘Bull’ Connor, Birmingham’s racist chief of police. All the protestors were carted off to the Birmingham city jail, including Dr. King. And that is where Dr. King penned his famous letter.

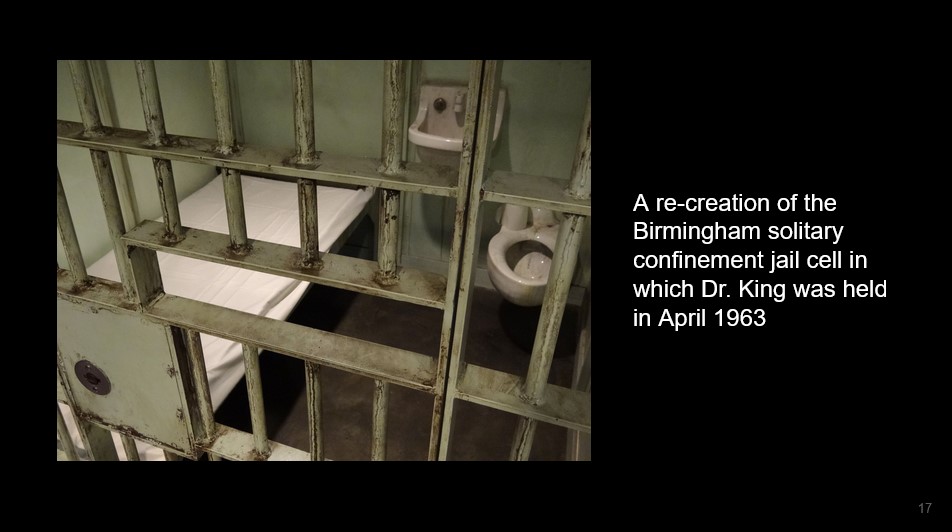

The story of Dr. King’s letter doesn’t end there though. Because Dr. King wasn’t just any prisoner. He was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the civil rights movement. And so ‘Bull’ Connor had to make an example out of him, and he ordered that Dr. King be placed in solitary confinement, where he would be cut off entirely from the outside world.

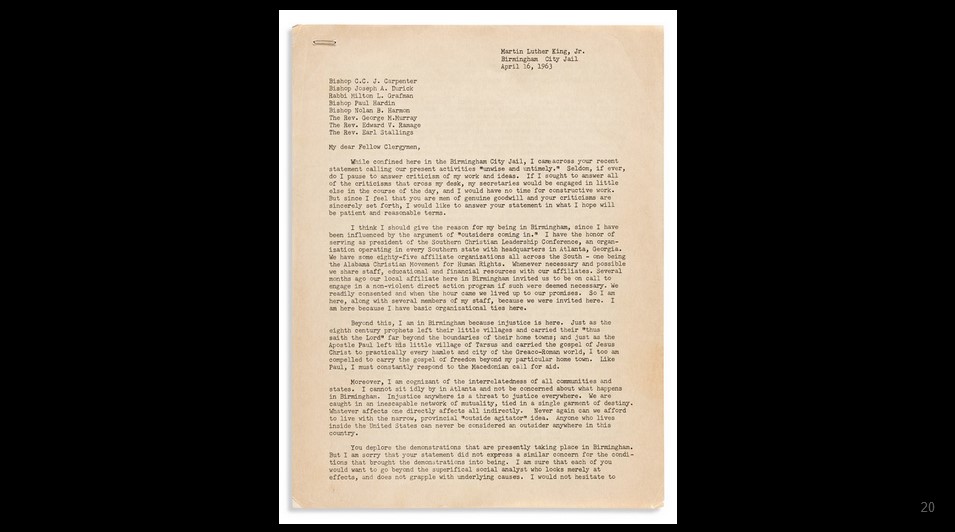

If you’ve read the ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ you know that Dr. King actually wrote the letter as a response to something. This something was also a letter, but not one addressed directly to Dr. King. It was an ‘open letter’ signed by 8 Birmingham religious leaders and published the day after Dr. King was arrested as a full page ad in The Birmingham News, the city’s leading newspaper. In their open letter the religious leaders criticised the tactics and the timing of the recent demonstrations in Birmingham, organized and led in part by Dr. King himself.

Because Dr. King was in solitary confinement there was no way he would have seen this open letter. He didn’t even have access to his lawyers let alone newspapers. Someone though managed to smuggle a copy of The Birmingham News into the jail for Dr. King. Whoever this person was, he or she would end up changing the course of history.

After Dr. King read the ‘open letter’ something clicked in him. He was like a man possessed. He had to respond. Some way, somehow. He didn’t have any writing paper. He didn’t have any books or notes to which he could refer. All he had was the smuggled newspaper and his own wits. So he started to draft a response on the newspaper itself, writing in the margins and in any blank space he could find. When he filled up the newspaper, he switched to writing on any piece of scrap paper he could find. Toilet paper, paper towels, and eventually paper scraps and a pad of paper that Clarence Jones, a lawyer for Dr. King, smuggled into the jail.

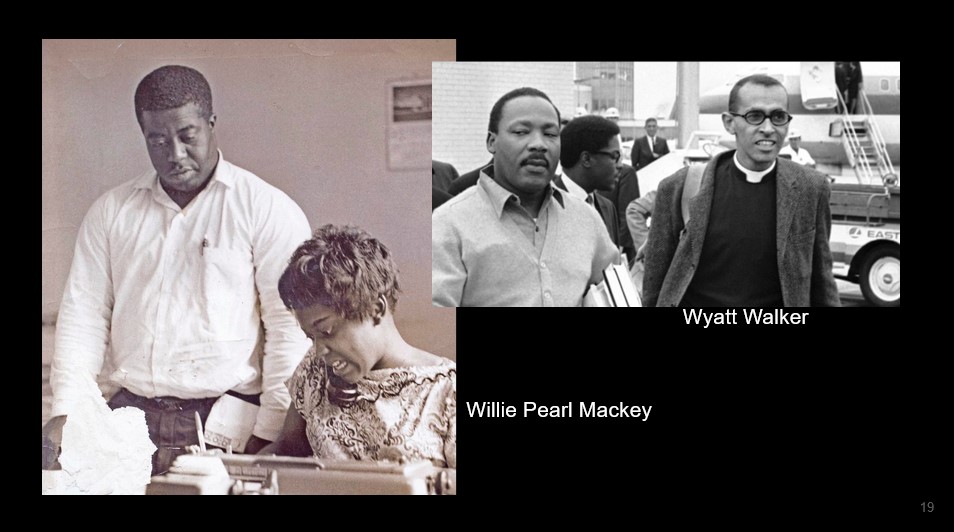

Every single piece of paper scrap that Dr. King wrote on was in turn smuggled out of the jail, also by Jones. And they eventually ended up in the hands of two people: Wyatt Walker and Willie Pearl Mackey, both allies of Dr. King. It was Ms Mackey’s job to transcribe all of Dr. King’s paper scraps that crossed her desk, at least the ones she could read. She worked night and day, sometimes to the point of complete exhaustion, to decipher, assemble and type up what Dr. King wrote. On April 16, 1963 the letter was finally finished. Some 7,000 words, twenty-one, double-spaced, typed pages. Dr. King left the Birmingham city jail on April 20, 1963.

Five years later, on April 4, 1968, a racist by the name of James Earl Ray armed with a high powered rifle, fired a single bullet into the head of Dr. King, killing him. Dr. King was 39 years old at the time.

When I selected Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail as the text for this talk I didn’t know any of the story behind how the letter came about. I knew generally of the history of the civil rights movement that Dr. King helped lead, but there were many details about the movement that I had either forgotten about or just didn’t know at all until now. In re-reading the letter and piecing together the story behind it, I cannot help but think about Hong Kong, and how many people here, including myself, experienced our own version of the civil rights movement. We experienced it with our bodies. We experienced it with our minds. And we experienced it with our souls.

I know what you all might be thinking to yourselves now, or maybe you’re whispering to your neighbor this very thought as it occurs to you: “he said ‘experienced’! But it’s not over yet!” And you might be right. Who in their right mind would think that a social movement involving millions of people can be so easily snuffed out only after a few months or perhaps a year of activity and protest?

One of the criticisms leveled against Dr. King which he adamantly rejected and specifically responded to in his famous letter from jail, had to do with time and tactics; the criticism being that Dr. King was acting rashly and even irresponsibly in trying to force the hand of the city by taking his case to the streets instead of to more official forums like the courts. If I’m not mistaken some people made a similar criticism in relation to the 2019 protests in Hong Kong.

If I may I would like to share with everyone some of what Dr. King wrote in response to this criticism.

First, with respect to the criticism about tactics —

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creating the tension as part of the work of the nonviolent-resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

from Letter From a Birmingham Jail collected in Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King Jr., pp. 78-79 (Signet Books 1964).

That was Dr. King responding to those who disagreed with his use of public protest and civil disobedience as tools for social change.

Now here he is responding to the criticism that he was being impatient in not waiting for lawmakers or judges to act.

I had also hoped that the white moderate would reject the myth concerning time in relation to the struggle for freedom. I have just received a letter from a white brother in Texas. He writes: “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but it is possible that you are in too great a religious hurry. It has taken Christianity almost two thousand years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” Such an attitude stems from a tragic misconception of time, from the strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually, time itself is neutral; it can be used either destructively or constructively. More and more I feel that people of ill will have used time much more effectively than have the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. Human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co-workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right. Now is the time to make the real promise of democracy and transform our pending national elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. Now is the time to lift our national policy from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of human dignity.

from Letter From a Birmingham Jail collected in Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King Jr., pg. 86 (Signet Books 1964).

Reading and thinking about this now in the context of Hong Kong I am of the feeling that some of what Dr. King wrote in his letter might not apply to the Hong Kong of today. We must remember that during Dr. King’s time and the time of the civil rights movement, the United States was still mostly a democracy. By that I mean a country with a government whose priority was responding to and caring for its people rather than amassing and maintaining power.

It was a time when activists did go to the courts to overturn racist laws, and sometimes won. It was a time when presidents, personally and through their use of federal resources, intervened in the affairs of state and local governments that were reluctant and unwilling to change their racist ways, even when the laws ordered them to. It was a time when lawmakers worked hand in hand with civilians to craft laws for the greater good of the nation rather than for the pocketbook of the businessman.

And so when Dr. King wrote his letter from the city jail and called for more not less direct-action to force the kind of ‘constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth’, he was operating under two, not unrealistic assumptions: one, that the people responsible for creating this kind of tension were very much in harm’s way, AND two, that these people had allies inside the existing power structure who would be willing to enter the fray on their behalf in the event all hell broke loose.

In Hong Kong today there are still many people who could be considered in harm’s way but I imagine that no official in a position of power would be willing to go to bat for any of them.

Does this mean that Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail has nothing to teach those in Hong Kong who are hoping to find a peaceful resolution to what ails the city now and in the future? No. Many who read the letter will certainly see it as a political and tactical playbook for how to challenge the status quo. Much like the ‘The Power of the Powerless’, the famous essay by the late writer and first president of the Czech Republic, Vaclav Havel.

But also like Havel’s book, Dr. King’s letter is more than just a how-to manual. It is a document of faith, of love, of hope. It is a document that rejects the cynicism of the many who believe that the best and only kind of change is the change in one’s bank account. It is a document that would give a lawyer the courage and reason to turn over a new leaf and become a bookseller in a city he’s never lived or worked in. It is a document that can turn an otherwise ordinary bookshop into an extension of one’s home, a place of warmth and love, and one that can provide a fellow booklover and dear friend with what this person has described as ‘the best job in the world’.

In other words, the Letter from Birmingham Jail is exactly the kind of document that Dr. King set out to write. It changed my life in the best ways, both big and small, and I think it might do the same for you.