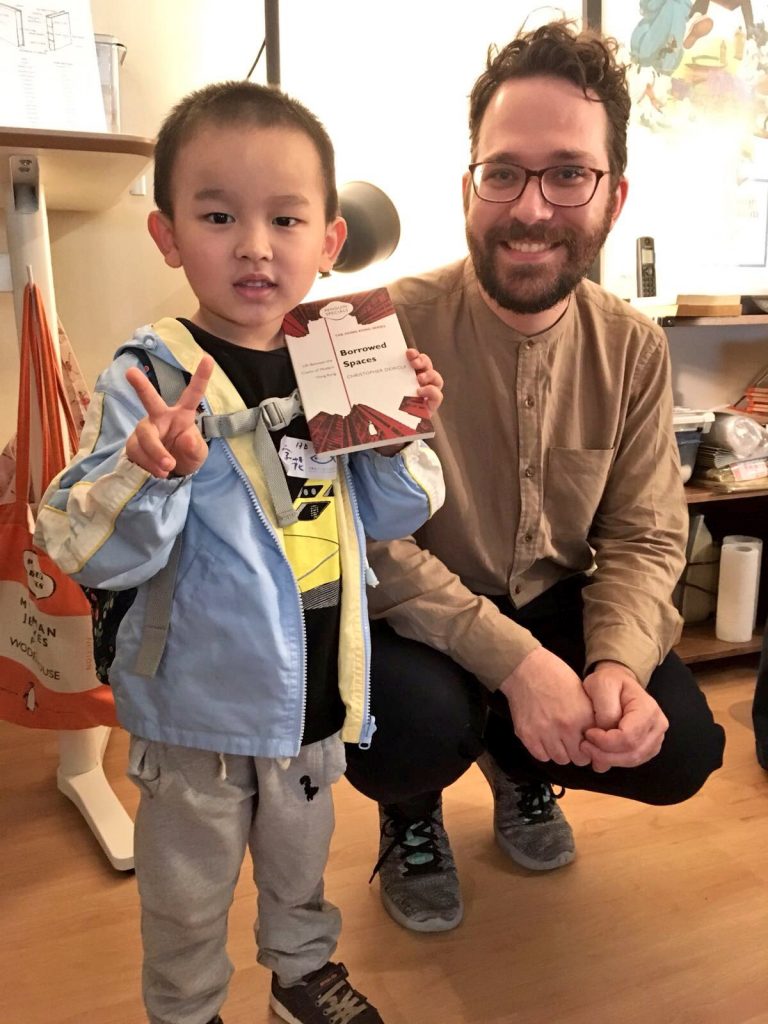

For last year’s San Po Kong Arts Festival we invited Christopher DeWolf to the bookshop to talk to festival-goers about San Po Kong and how it has been changing in the past few years, along with the rest of Hong Kong. He was such a hit that we asked Christopher to make a return visit for this year’s SPK Arts Festival but Christopher couldn’t make it. Instead, he has contributed a piece, which he wrote exclusively for the Arts Festival, in which he discusses San Po Kong’s forgotten history, what’s left of that history in today’s San Po Kong, and what might be in store for the San Po Kong of tomorrow.

Everything You Can’t See

In San Po Kong

by Christopher DeWolf

In San Po Kong, what you see is not what you get. At first, it seems interchangeable with many other parts of Hong Kong – the kind of neighbourhood that, if it were a television show, would be a generic TVB drama, the kind whose characters and plot twists you have seen countless times before.

Just look at it. There are industrial streets with hulking concrete warehouses, others with rows of working-class tong lau. Two massive housing estates rise on the neighbourhood’s fringes, one humble in appearance, with anonymous towers punctured by small windows, the other more extravagant, with a glitzy shopping mall capped by a private roof garden, above which soar high-rise blocks with large balconies and floor-to-ceiling windows. So far, so typical.

But San Po Kong is deceptive. Deep inside its industrial buildings are coffee roasters and craft brewers, painters and photographers. An exceptionally well-curated collection of books hides inside one anonymous commercial tower; the King of Soyabeans purveys Michelin-recommended Shanghai-style sticky rice rolls from the base of another. And floating around all of this is a 700-year history that shaped Hong Kong into the city it is today.

On a map, San Po Kong looks like an island. It is a tight grid of streets wedged into a kidney-shaped parcel of land that floats between the Kai Tak River on one side and the vast lands of the former Kai Tak Airport on the other. The entire neighbourhood covers less than half a square kilometre, but it is home to 24,000 people, a density that infuses its streets with a constant thrum of energy. You can walk from one end to the other in less than 10 minutes.

And yet a walk through San Po Kong reveals a richness of history and culture that should never be taken for granted. In the middle of the 14th century, a man named Ng Chung-tak settled with his family on the shores of a stream that flowed into Victoria Harbour. Ng was the patriarch of a large family that had three centuries earlier fled the northern edge of Guangdong province to escape the chaos of the collapsing Song dynasty. The family eventually splintered across Guangdong and Vietnam, but Ng Chung-tak’s branch made their way to Kowloon. In 1354, they built a temple in honour of Tin Hau in their new settlement, which eventually became known as Nga Tsin Wai.

Nga Tsin Wai is still there – in a way. After seven centuries as a walled village, it has now been mostly demolished by the Urban Renewal Authority to make way for luxury housing and a sort of heritage theme park. The area around it has changed beyond all recognition. Once a fertile plain ringed by hills, with a sandy beach along what is now Prince Edward Road East, its geography was altered in the early 20th century when a pair of entrepreneurs named Kai and Tak pooled their resources to fill in the waterfront, creating space for Hong Kong’s first airport.

If you cross the bridge from Nga Tsin Wai today, you will reach the heart of San Po Kong’s market district, where stands of fresh fruits and vegetables spill out onto concrete pavements. This development dates back only to the late 1950s, but it was long ago home to the village of Po Kong, which was settled by the Lam family some time after Nga Tsin Wai. Other nearby villages had banded together into an alliance known as the League of Seven, but Po Kong was an outlier, with its own Tin Hau temple that stood in rivalry to that of its neighbour.

For most of its history, Po Kong was a large and prosperous agricultural settlement, but its fortunes were tested by an influx of squatters in the 1930s. They built houses on Po Kong’s fields and refused to pay rent, throwing the village’s economy into chaos. Villagers blamed this misfortune on Tin Hau’s failure to provide protection, and in revenge they set her figure aflame. Po Kong’s neighbours in Nga Tsin Wai were aghast, and they were not surprised when Po Kong suffered a far greater indignity less than a decade later. After Hong Kong was invaded by the Japanese military in 1941, its new occupiers decided to expand Kai Tak Airport, wiping Po Kong off the map in a matter of weeks.

San Po Kong (“New Po Kong”) was one of the new industrial suburbs planned by the colonial British government to satisfy Hong Kong’s postwar economic boom. In 1967, a labour dispute at an artificial flower factory on Tai Yau Street mushroomed into six months of intense riots. The villagers of Nga Tsin Wai locked their gate and stood guard, ready to do battle if necessary. It seems they were still wary of Po Kong – even the new version.

Very little of this history is apparent when you walk around San Po Kong. There are no historical plaques, no acknowledgement of the centuries of history that have shaped this corner of Hong Kong. By contrast, the future of the neighbourhood is easier to divine. The former airport is now being redeveloped as a residential, commercial and entertainment district, complete with a monorail and major sports stadium. A new MTR station is under construction. And beyond that, the nearby districts of Kowloon Bay and Kwun Tong have been designated by the government as CBD2 – a new central business district.

You can already see how San Po Kong is changing as a result. New hotels have cropped up in the old industrial area, bringing with them tourists and the shops that cater to them. Factory buildings are being knocked down and replaced by office towers. As always, it’s easy to see the broad outline of what is happening to the neighbourhood. But the details are harder to read. It could well be that San Po Kong still has the potential to surprise.

Christopher DeWolf is a journalist who has written about cities, history, design, culture, travel, food and drink for more than 15 years. His first book, Borrowed Spaces: Life Between the Cracks of Modern Hong Kong (Penguin 2016), explores grassroots efforts to improve urban life. He is a regular contributor to South China Morning Post and Zolima CityMag. Christopher considers San Po Kong the ‘quintessential Hong Kong neighbourhood’, Pentahotel and all.